Table of Contents

Topic Introduction

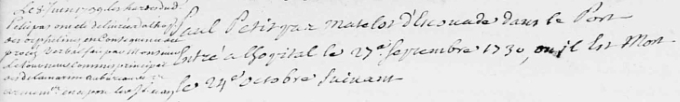

Death of Barthélemy Petitpas

Barthélemy Petitpas, William Shirley and The Treaty of Utrecht

Barthélemy Petitpas, William Shirley and The Treaty of Utrecht Continued

Barthélemy Petitpas, William Shirley and The Treaty of Utrecht Continued

William Shirley and Barthélemy Petitpas Continued

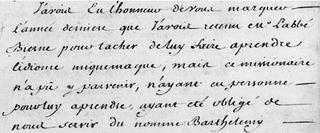

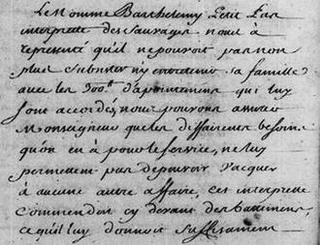

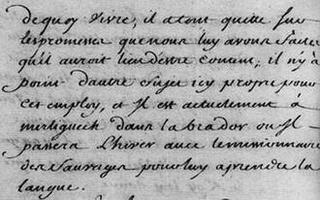

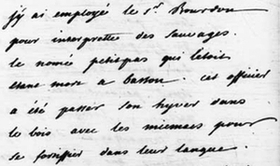

The How and When of The Petitpas' as Interpreter for The Indians

Father Maillard's Account of Barthélemy Petitpas' Death

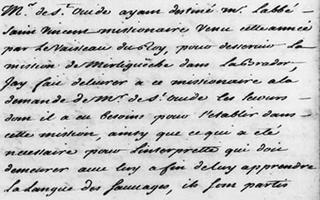

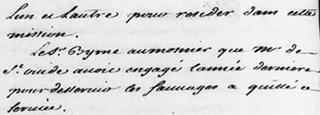

Barthélemy Petitpas' Biography and The Year 1722

Barthélemy Petitpas was Mistaken for Someone Else

Emma Lewis Coleman and The Petitpas' Biographies

Claude Petitpas II in his Biography was Mistaken for Someone Else

Collection de Manuscrits Relatifs à la Nouvelle-France (CMRNF) Vol. III Continued

Claude Petitpas II was Mistaken for Someone Else Continued

Claude Petitpas II’s biography Continued – The Mi'Kmaq Question Considered

Claude Petitpas II and Sons Living Under English Domination

Claude Petitpas II and Sons Living Under French Domination

No Evidence Found That Barthélemy was a Guest of The English

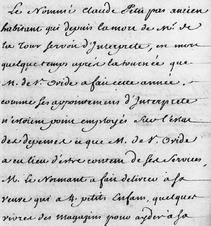

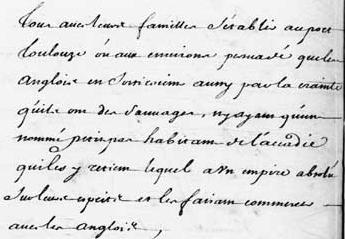

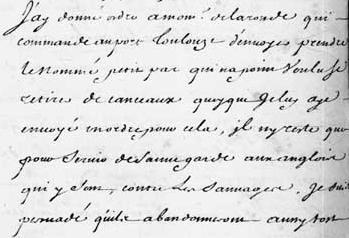

Stories About Les Nommés Petitpas

Barthélemy Petitpas' Biography Research Continued

Identifying The 1722 Young Petitpas & Two of His First Brothers

Identifying The 1722 Young Petitpas & Two of His First Brothers Continued

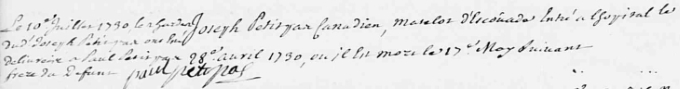

More about Full Brothers Isidore, Joseph & Paul Petitpas

Fate of the Full Brothers Isidore, Joseph & Paul Petitpas

Substantial Errors and Omissions in Les Nommés Petitpas Biographies

Short Summary to Salute Claude II's and His Eldest Son Barthélemy's Lives

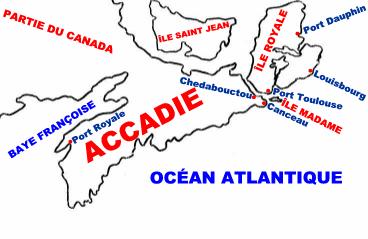

Sketch of Area Back Then

Source

Other Internal Pages on this Website: A1, A2, B26, B29, B30, B31, D5, H2, H5, H6, H7, H12 & H19

Supplementary Notes

French Version of This Website

This Web page was successfully checked as HTML5

This Web page was successfully checked as HTML5

Topic Introduction

The year 2004 marked the 400th anniversary and celebration of the founding of the French settlement in the colony of Acadie in New France. The year 2008 marked the 400th anniversary and celebration of the founding of the French settlement in the colony of Canada in New France. Salute to “les Acadiens/Acadiennes” and “les Canadiens/Canadiennes” of the colonial era.

Several times the domination of Acadie changed between Great Britain and France. In 1713 the swinging back and forth of Acadie’s domination ended by the Treaty of Utrecht (March 31 – April 11, 1713). The signing of this treaty ended the war for the Spanish Succession known in North America as the Queen Anne’s War. France gave up claim to Acadie (now named - Nova Scotia) and retained Île Royale (now – Cape Breton Island). After April 11, 1713, one condition of the treaty was that anyone living and staying under the domination of Great Britain regardless of their ancestry would need to comply with the laws of Great Britain. The French did not totally abandon the Acadians by signing the Treaty of Utrecht; there was a clause that allowed them to relocate to other French colonies. Eventually and fortunately some Acadians did emigrate to the new French colony Île Royale before the Exile of the Acadians in 1755. However it turned out that this was no safe residence for Acadians. In 1763, France by the Treaty of Paris ceded all of New France to Great Britain. The exception was Saint-Pierre et Miquelon. A lot of the geographical names of Acadie were renamed. Baye Françoise was renamed Bay of Fundy. Some others renamed areas relating to this presentation are Port Royale to Annapolis Royal, Canceau to Canso and Port Toulouse to St Peters. Île Saint Jean became the Province of Prince Edward Island.The following sketch gives a French perspective of the area back then:Table

Les nommés Petitpas (Those named Petitpas) was how the French authority identified this Petitpas family in the 17th & 18th centuries.

Mostly this presentation contains and refers to copies of original documentation. It was put together to illustrate and hopefully clarify the inaccurate details of two biographies in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography/Dictionnaire biographique du Canada. These erroneous biographies are for Claude Petitpas II and his eldest son Barthélemy Petitpas. Claude Petitpas II's biography was published in the 1969 DCB/DBC volume II. Barthélemy Petitpas’ biography was published in the 1974 DCB/DBC volume III.

Also, these two biographies are available electronically at DCB/DBC Online:This presentation will also explain the effect that the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht had on Claude Petitpas II and his first four sons; while under English and French domination in the colonies.

Death of Barthélemy Petitpas

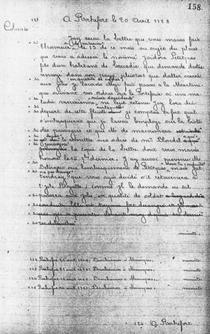

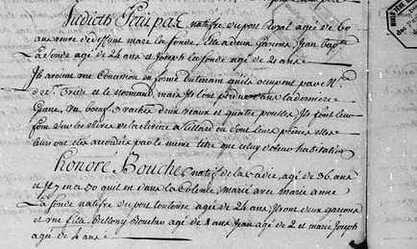

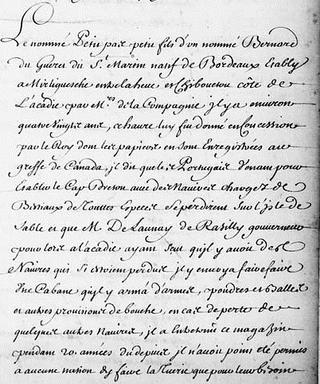

This research report story begins by the review of a copied original record which officially declares Barthélemy Petitpas dead. The year is 1750 and the hearing place is at Louisbourg in the then French colony named Île Royale (now – Cape Breton Island). The King George’s War from 1744 to 1748 was over. Louisbourg which had been captured during the war by the New England force was returned to France by the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.Library and Archives Canada (LAC) Website has 2 digital image copy pages of an original handwritten documentB1. Below the scope and content of this document dated October 9, 1750 says:

“Jean Jacques Brunet, négociant et demeurant en cette ville, George Barbudeau, chirurgien résidant au havre du Saint-Esprit en cette isle de présent en cette ville, et Pierre Brisson, habitant de l'Ardoise, lesquels ont affirmé par serment que Barthelemy Petitpas, interprète des sauvages en cette colonie est mort dans les cachots des prisons de Baston, en Nouvelle Angleterre, au mois de janvier de l'année 1747, au quel temps les trois étaient prisonniers dans la dite ville.”Above translated freely: Jean Jacques Brunet, negotiator and living in this town, George Barbudeau, surgeon and a resident of Havre St Esprit on this island and present in this town, and Pierre Brisson inhabitant of l'Ardoise, all affirm by oath that Barthelemy Petitpas, Interpreter for the Indians in this colony died in the dungeons of the prisons of Baston in New England, in the Month of January of the year 1747, at the time the three were prisoners in that town.

LAC Website has another digitized 3 pages copy of an original handwritten documentB2 dated April 12, 1749.

The scope and content states this:

“Gervais Brisset, oncle du côté maternel, a été choisi comme le subrogé tuteur de Jean, Pierre, Claude, Guillaume, Paul et Pelagie Petitpas, enfants issus de la communauté de Madelaine Coste, et de feu Barthelemy Petitpas, de son vivant, interprète des Sauvages de cette colonie.”Above translated freely: Gervais Brisset uncle on the maternal side, was chosen to be the subrogated tutor of Jean, Pierre, Claude, Guillaume, Paul and Pelagie Petitpas from the life of Magdelaine Coste and the deceased Barthelemy Petitpas during his life was Interpreter for the Indians in this colony.

It appears, the above record indicates that French Authority was aware, and considered or declared Barthélemy Petitpas dead as far back as April 12, 1749.

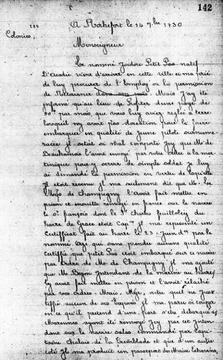

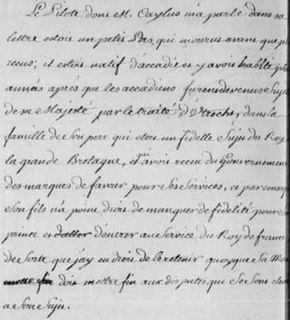

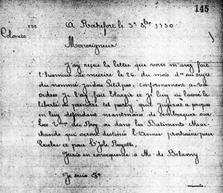

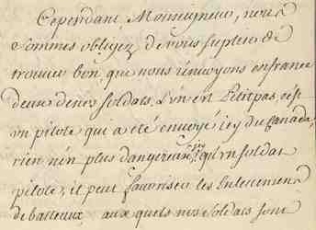

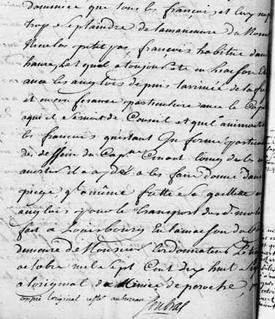

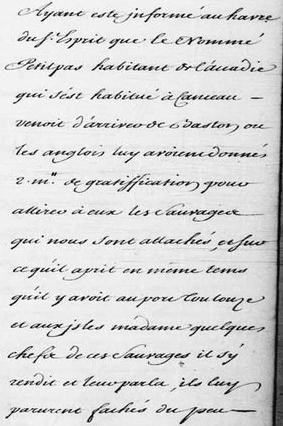

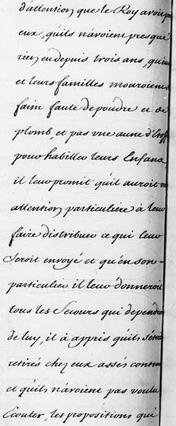

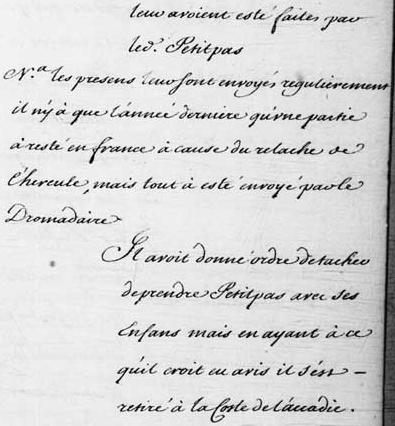

Furthermore, 2 digitized documents at LAC show French Authority had decease knowledge in 1747 about a pilot named Petitpas. Next are two records/letters between William Shirleyc1 Governor of Massachusetts and Charles de BeauharnoisA3.July 31, 1747 – Letter from William Shirley, governor of Massachusetts, to Charles de Beauharnois. It must be emphasized and noted the above mentioned “Shirley” is the same William Shirley along with the acting Governor Charles LawrenceA4 of Nova Scotia (Acadie) who planned and cooperated in the Exile of thousands of Acadian men, women and children by ships to other Colonies. This resulted in many of them dying a horrendous death. Also, this man is the same who had declared war against the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet (Malecite) people in 1744 with the British proclamation of scalpingP6.P1. This contextual information illustrates with which manners the governor could treat the Acadian and Mi’kmaq people and how this had a negative impact on the fate of Barthélémy Petitpas. Apparently, in this 3 page letter from Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts (less than 10 years prior to the mass Exile of the Acadians), he was trying to justify what he had done to France's Official Interpreter for the Indians - Barthélemy Petitpas. The following is an excerpt (see image 288v) of the 3 pages documentB3A at the Online LAC Website:P11.P8

Excerpt translated freely: The Pilot that M. Caylus talked about in his letter was a petit Pas [Petitpas] who died before I received it. He was a native of Accadie who lived more years after the Accadians became subjects to his Majesty by the Treaty of Utrecht in the family of his father who was a faithful subject of the King of Great Britain and received from the government marks of favors for his services, and consequently his son has lack of faithfulness for the prince and entered the services for the King of France. So that I had the right to detain him, although his death must end the disputes about him.

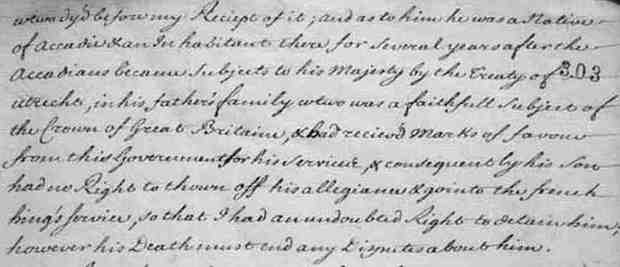

Excerpt translated freely: The Pilot that M. Caylus talked about in his letter was a petit Pas [Petitpas] who died before I received it. He was a native of Accadie who lived more years after the Accadians became subjects to his Majesty by the Treaty of Utrecht in the family of his father who was a faithful subject of the King of Great Britain and received from the government marks of favors for his services, and consequently his son has lack of faithfulness for the prince and entered the services for the King of France. So that I had the right to detain him, although his death must end the disputes about him.The above document at LAC is a translation of Shirley's July 31, 1747 letter. LAC has a transcription of Shirley's letterB3B. Below are excerpts of the transcription folios (302v & 303) about the pilot named Petitpas:

Above transcribed freely: The pilot mention'd in Mr. Caylus's letter was one Petitpas who died before my receipt of it, and as to him he was a native of Accadie and an inhabitant there for several years after the Accadians became subjects to His Majesty by the treaty of Utrecht, in his father's family who was a faithfull subject of the crown of Great Britain, & had received marks of favour from this government for his services, & consequently his son had no right to throw off his allegiance and go into the french King's service, so that I had an undoubted right to detain him, however his death must end any disputes about him.

It must be emphasized that the English and the French were disagreeing and claiming about whose Subject Barthélemy was in correspondences between Beauharnois and Shirley in 1747. This is assuming that Barthélemy Petitpas was indeed the pilot named Petitpas. The July 31, 1747 transcribed letter from William Shirley, governor of Massachusetts, to Charles de Beauharnois is found on page 379 of the book titled Collection de Manuscrits Relatifs à la Nouvelle-France Vol. IIID1. Later on there is more notation about the (CMRNF Vol. III) documents that were references for Claude II (page 38 - 39, 379) and Barthélemy Petitpas' (page 379) biographies at DCB Online. The next excerpt of page 379 from the collection is regarding the pilot named Petitpas:P15.P3

Above transcribed freely: The pilot mention'd in Mr. Caylus's letter was one Petipas [Petitpas] who died before my receipt of it, and as to him he was a native of Accadie and an inhabitant there for several years after the Accadians became subjects to His Majesty by the treaty of Utrecht, in his farthr's family who (?) was a faithfull subject of the crown of Great Britain, and had received marks of favour from this government for his services, and consequently his son had no right to throw off his allegiance and go into the french King's service, so that I had an undoubted right to detain him, however his death must end any dispute about him.

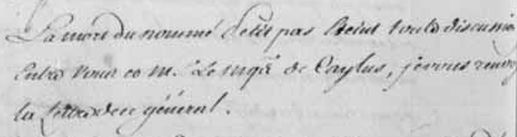

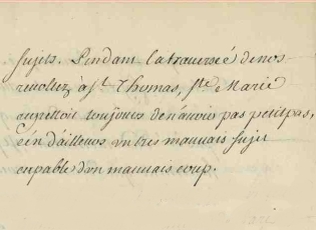

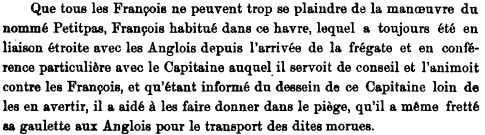

Sept. 16, 1747 - Copy of the letter from Marquis de Beauharnois to William Shirley, governor of Massachusetts. The 3 digitized images of the original handwritten document B4 can be viewed at the LAC Website. Apparently, the next excerpt of this letter (Image 296v) is the acknowledgment from France of Barthélemy Petitpas' death:

Above translated freely: The death of the one named Petitpas ends all discussions between you and M. le Mgr de Caylus, I am sending back to you the letter of this General.

No records about Petitpas were found at the Online Massachusetts searchable, descriptive index Archives Website. However from the above documents it can be concluded that France acknowledged Barthélemy Petitpas' death.

Barthélemy Petitpas, William Shirley and The Treaty of Utrecht

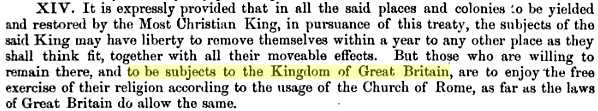

The historians (from DCB Online) who wrote the Petitpas biographies for Claude II and his son Barthélemy did not mention the Treaty of Utrecht (March 31 – April 11, 1713).Ironically, as previously mentioned William Shirley apparently used the Treaty of Utrecht to justify the death of Barthélemy Petitpas who should have had rights according to the treaty as an Acadian and as an American Native Mi'Kmaq Indian. The specifics would be outlined in Article XIV and XV. It is very unlikely that William Shirley was not aware of this.

In his letter dated July 31, 1747, William Shirley corresponds that “Accadians became subjects to His Majesty by the treaty of Utrecht”. It had been a long time since Barthélemy and his father Claude II had emigrated to the French colony Île Royale (now – Cape Breton Island). How could William Shirley so unreasonably declare Barthélemy Petitpas a subject of Great Britain? The answer to this is most likely in the translation of the original Latin Treaty of Utrecht document to English and William Shirley himself.

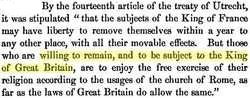

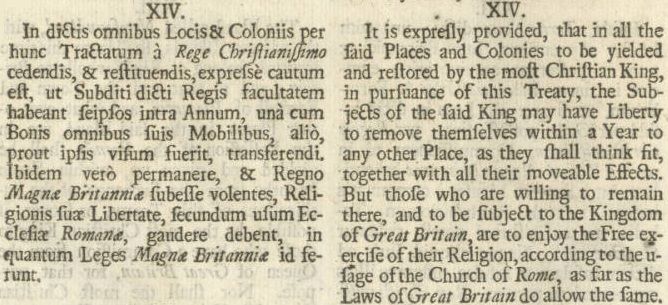

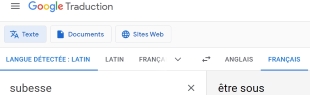

The Early Canadiana Online (ECO) Website shows the following concerning the Treaty of Utrecht Article XIV:

"XIV. It is expressly provided, that in all the said places and colonies to be yielded and restored by the most Christian King, in pursuance of this treaty, the subjects of the said King may have liberty to remove themselves within a year to any other place, as they shall think fit, together with all their moveable effects. But those who are willing to remain there, and to be subject to the kingdom of Great Britain, are to enjoy the free exercise of their religion, according to the usage of the church of Rome, as far as the laws of Great Britain do allow the same."

This documentE1 can be seen at the ECO Website. After reading the above Article XIV someone could say this could imply that William Shirley's argument was that Barthélemy had not removed himself from Acadie (Nova Scotia) within one year so he became a subject of Great Britain.However, the ECO Website has the complete French translated version of the Treaty of Utrecht. The above highlighted word subject is not the proper word to use in translation because it could be misleading. Also if the word domination is translated in English as the word domination is used as in the French version, then the Article XIV takes a clear interpretation that the Acadians who chose to remain in Acadie (Nova Scotia) after one year would still remain as French subjects. There is nothing in Article XIV that says the Acadians who did not go elsewhere within the year would have renounced themselves as being subjects of France. Below for this research, Article XIV has been translated to English from the French version at the ECO Website. *2As of this writing the original Latin version Treaty of Utrecht has not been found for comparison and verification.

Article XIV translated freely:P3.P9 It is expressly agreed, that in all places and colonies that must be yielded or returned by the most Christian King, in accordance to this Treaty, the subjects of the said King will have the liberty to withdraw elsewhere within the time of one year with all their moveable things that they can transport where they so please; those nevertheless who would like to live and stay under the domination of Great Britain will enjoy the exercise of the Roman Catholic Religion as far as permitted by the laws of Great Britain.

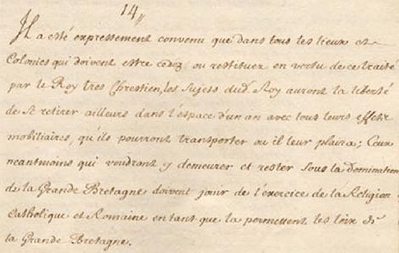

As indicated, ECO Website has the documentE2 with Article XIV in French that was used to translate the above or see the below excerpt:

The French handwritten Article XIVF1 document copy is available at Archives Canada-France Website or see the below graphic excerpt:

Also, at Archives Canada-France Website there is: The EdictF2 from Queen Anne of Great Britain for the Acadians dated June 23, 1713, and the ProclamationF3 April 19, 1720 from Richard Phillips, Governor of Nova Scotia to the Acadians telling them to swear an oath of allegiance to the King of Great Britain or leave the province. Queen Anne of Great Britain in the Edict dated June 23, 1713 refers to the Acadians that would stay in Nova Scotia as their (Great Britain's) subjects.

As stated above the word subjects is not stated pertaining to Great Britain in Article XIV Treaty of Utrecht (See Article XIV translated freely, P3.P6). The Website 1755 The History and the Stories by the Centre D'Études Acadiennes of the Université de Moncton has a transcriptc2 of the (letter) Edict.This research found no amendment to Article XIV of the Treaty of Utrecht.

Subsequently to the above writing (see P3.P5*2) a Latin to English translation version of the Treaty of Utrecht Article XIV was found on the Internet.

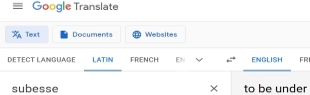

The documentH8 can be viewed and downloaded from Memorial University's Digital Archives Initiative Website of Newfoundland. Below is an excerpt of page 74, Article XIV translation from Latin to English:After the above Latin Article XIV was reviewed it indicates that the word ſubeſſe = subesse (Note: The letters that look like the letter f in the word “ſubeſſe” are the old Roman “long “s” letters). Subesse means “to be under” in English. The word "under" translates as “sous” which is the word translated in the Latin to French version of the Treaty of Utrecht Article XIV. In the English Article XIV the Latin word subesse was translated as the wording “to be subject to” instead of the wording “to be under” (Note: “sub = under” & “esse = to be” which means “to be under” in English & “sub = sous” & “esse = être” which means “être sous (to be under)” in French). If the Latin word subesse would have been translated as the word “to be under”; this would have resulted in the Latin to the English translation as “But those who are willing to remain there, and to be under the kingdom of Great Britain” in the English Article XIV. Actually, the above Latin Article XIV verifies that the word subjects is not stated pertaining to Great Britain in Article XIV Treaty of Utrecht. The Latin word "subditi" which means subjects in English and sujets in French only appears once pertaining to (the most Christian King) the French King's subjects. The Latin word "Regno" translation to English is correctly "Kingdom".

What could be misleading is the use of the mistranslated word subject as describe is that it can be misinterpreted and taken out of context. In other words, the use of the mistranslated word subject in the English Article XIV can be misread giving the impression to someone in misinterpreting the phrase as: “But those who are willing to remain there, and to be

subject[s] to the Kingdom of Great Britain,”.Having a “s” at the end of the word subject would indicate that Acadians who did not go elsewhere within a year would have renounced themselves as being subjects of France and become subjects of Great Britain.

The previous statement is not such an extreme point or an unrealistic hypothetical scenario. In fact, several Websites were found to have written the word “subject” in its plural form as "subjects" in their partial or whole quotation versions of article XIV. Some of the Websites were very well intended Acadian & Cajun informative historical and genealogical forums. Furthermore it should be noted that in some (present-day) legal translations of the word “subesse” has evolved incorrectly to mean “subject to”.

One more bookD11 that Google digitized title is: "Latin Synonyms, With Their Different Significations: And Examples Taken From The Best Latin Authors". The author's name was Jean Baptiste Gardin Dumesnil. His book was published by G.B. Whittaker, at London in 1825. It confirms that in the English language the latin word "subesse" translation or meaning is "to be under". Below is an excerpt from the book:

Furthermore, Google's Translation WebsiteD12 for the Latin words "subditi" and "subesse" are in accordance to the above researched translations:

Prior to this update as pointed out above, and in conclusion after reviewing the available Latin Article XIV of the Treaty of Utrecht:

- Queen Anne (16650206 - 17140801) of Great Britain in the Edict dated June 23, 1713 refers to those who would stay in Acadie & Terreneuve (Nova Scotia & Newfoundland) as our (Great Britain's) subjects. There is nothing in Article XIV that says the Acadians who did not go elsewhere within a year would have renounced themselves as being subjects of France and become subjects of Great Britain. As well, Article XIV does not say that Acadians who did not go elsewhere within a year would have lost their possessions.P4.P1

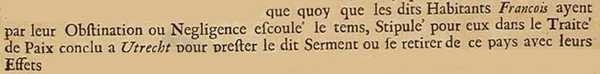

- Also nothing was found in the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 that said Acadians had to swear an oath of allegiance to her Majesty or Great Britain if they did not leave after one year. This is very puzzling & appears contradictory of the Proclamation of April 19, 1720 by Richard Phillips, Governor for Accadie (Nova Scotia) of his Majesty King George. In an excerpt of the Proclamation it states:

Above translated freely: that whatever the said François inhabitants have by their obstinacy or negligence drained the time, stipulated for them in the Treaty of Peace which was concluded at Utrecht to give the said oath or to withdraw from this country with their things

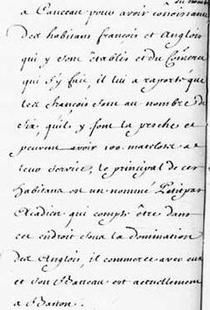

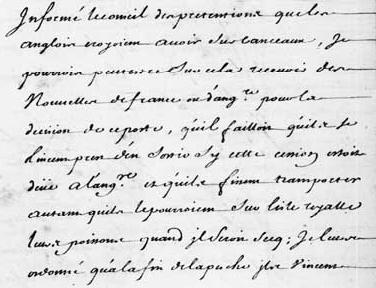

In addition for this research, many French documents dated after the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht were reviewed about "les nommés Petitpas". These documents were generated because of "les nommés Petitpas'" interaction with the French Authority. The French Authority referred to "les nommés Petitpas" at times, as Acadian, as French and as their Subject(s) (sometimes as “mauvais François” or “mauvais Sujet” meaning “bad Frenchman” or “bad Subject”) but never as Subjects of Great Britain. Neither did it matter where "les nommés Petitpas" lived. If M. St Ovide, the Governor of Île Royale thought that Claude Petitpas II (when living in Nova Scotia after the Treaty of Utrecht) was not living up to his expectations, M. St Ovide had no problem in sending French Authority to take "le nommé Petitpas". This applied to Claude II's young son which is explored at length later in this presentation. There are two records of this attempted captures which happened in late 1718 & 1719. It is look into further in below at P16.P2 & P16.P11. This happened after "le nommé Petitpas" had announced to French authority that he was in the Canceau area under English domination. The Louisbourg Institute of Cape Breton University - The Official Research Site for the Fortress of Louisbourg had a summaryG1 record of a letter dated November 30, 1717. LAC has a digitized copy of the original documentB5 relating to the Council's deliberation dated April 1, 1718 of the 15 page letter. It says when in English territory fishing such as Canceau Bay, the French Authority wrote that "le nommé Petitpas" said he was in the area under English domination. The statement is on page folio 18v - item and the next excerpt:

Excerpt translated freely: To be aware of the French and English inhabitants settled and the commerce that is taking place at Canceau. It was reported to him [Captain M. de la Ronde] that there are 6 Frenchman [françois] who do fishing and there could be 100 sailors working for them. The principal inhabitant is one named Petitpas, Acadian who says he is in this area under the domination of the English. He trades with them and his boat is now at Boston.

Excerpt translated freely: To be aware of the French and English inhabitants settled and the commerce that is taking place at Canceau. It was reported to him [Captain M. de la Ronde] that there are 6 Frenchman [françois] who do fishing and there could be 100 sailors working for them. The principal inhabitant is one named Petitpas, Acadian who says he is in this area under the domination of the English. He trades with them and his boat is now at Boston.This leads to the realization that France considered Acadians living in Acadie under English domination as France’s Subjects. Acadians remained as such according to the French translation of the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) as described previously. In other words, the French did not cede the Acadians to the English only the territory Acadie with the expectation of loyalty from Acadians. Of course the English did not see it that way. Finally, this led to the barbaric actions taken by Great Britain and its colonial force in 1755 and continued for many years. This was the mass Exile of the Acadians known as the French Neutrals from their homeland. The word deportation is not utilized in this presentation to describe the agony of the Acadians. They were not the aliens in Acadie thus the word exile is used.

Barthélemy Petitpas, William Shirley and The Treaty of Utrecht Continued

P3.P19Just because Queen Anne refers to the Acadians as (nos Sujets) our Subjects, didn't make Acadians in legal terms Great Britain's Subjects. She would have required an amendment to the Treaty of Utrecht which would have involved having an agreement with the King of France.It is not thought that Queen Anne wrote something (herself) knowingly to mislead. However, some of the seeds were planted with her Edict to give an appearance that Acadians were Great Britain's Subjects if they did not leave within a year which was not indicated in the Treaty of Utrecht. Of course what helped this appearance was that in the English Article XIV, the Latin word subesse was translated as the wording “to be subject to” instead of the wording “to be under”.

Quite a number of the Acadians were very savvy or educated people and most would know the Latin and English languages. Therefore, Article XIV of the Treaty of Utrecht would be very clear to them that they were not British Subjects after a year. That is why they stayed in Acadie (Nova Scotia) and did not relocate to the other French colonies, Île Royale and Canada. Also, the Acadians knew by giving an unconditional oath it would make them British Subjects.

The Acadians were not British Subjects; this point is supported in a legal manner by Article XIV of the Treaty of Utrecht. In addition, this is supported by the actions of the French, the Aboriginals and the English during about the time period of 1713 -1755. Also, of course the actions of the Acadians themselves.

The Acadians and the French were reading and applying the Treaty of Utrecht as they saw it from a Latin to French translation. Of course, the English and its colonial force were reading and applying the Treaty of Utrecht as they saw it from Latin to English translation. One can just picture in their minds the colonial English and French Governors arguing over disputed territories (no it says that... – your wrong it says that...).

As said before, the word subject must not be written in its plural form (as subjects in regards to the phrase "and to be subject to the kingdom of Great Britain") because it vastly changes the context of Article XIV. This may have originally started as a old writing error and/or in more recent times as a typing error. However, a surprising fact was uncovered by a Google Web search. The search phrase with the search operator quotations marks was: "to be subjects to the kingdom of Great Britain". Quite a few results from Websites were found that had that incorrect phrase. Of course the "s" at the end of the word subjects found in the Google search results about Article XIV of the Treaty of Utrecht were errors. One bookD7 that Google digitized was published in 1878 and its title is: "Statutes, Documents and Papers Bearing on the Discussion Respecting the Northern and Western Boundaries of the Province of Ontario, Including the Principal Evidence Supposed to be Either for Or Against the Claims of the Province". An interesting fact is that the book digitized by Google was published over 135 years ago, and originally from Harvard University and part of the Harvard Law Library. Next is an excerpt of page 17 from the book:

There were several other digitized Google eBooks and documents found that have a different error that vastly changes the context of Article XIV. In their cases it was not by adding a letter “s” to the end of the word subject but by the omitted last three letters from the word Kingdom. There are three documents with that error listed in this presentation's "Source D" as Der1, Der2 and Der3.

To continue, it may well be that the English unintentionally viewed, were seeing or saw (imagined) a “s” on the end of the word subject. That would be for the involvements of Queen Anne (16650206 - 17140801) of Great Britain, Governor Charles Lawrence and William Shirley etc.. That said they thought that the Acadians who did not leave within a year automatically became British Subjects. It very well could be that the English were aware that the Treaty of Utrecht wording or its articles did not make the Acadians British Subjects after one year. Could it be that is why the English were so adamant in trying to get the Acadians to swear an oath of allegiance to them? Why ask for a unconditional oath if they were British Subjects after a year in 1714? It was immoral for the English to insist that the Acadians had to sign an oath that would compel them to bear arms against the French and the Aboriginals.

The 1763 Treaty of ParisH13 article 4 is quite clear in the wording in referring to the the inhabitants of Canada (Canadiens/Canadiennes) as being "new Roman Catholic Subjects" of his Majesty of Great Britain. In addition article 4, clearly states "that the French inhabitants, or others who had been subjects of the Most Christian King in Canada".

Furthermore, lets not forget the Proclamation of April 19, 1720 by Richard Phillips, Governor for Acadie (Nova Scotia) when he tried to make the Acadians believe that it was stipulated in the Treaty of Utrecht as follows:

Translated freely: “that whatever the said François inhabitants have by their obstinacy or negligence drained the time, stipulated for them in the Treaty of Peace which was concluded at Utrecht to give the said oath or to withdraw from this country with their things”Acadians knew that they were French Subjects living in a territory ceded to Great Britain according to the Treaty of Utrecht.

Acadians were distinct people who had no say in their domination at a particular time. The first Acadians and their descendants had live for over 150 years in union and amicably with the Aboriginals.

Just because the Acadians were coerced or forced on to vessels to be exiled to British colonies or England, and apparently the French doing very little to stop the exile doesn't make the Acadians less of as being French Subjects according to the Treaty of Utrecht.

Warren A. PerrinH14 in his PetitionH15 (that resulted in the Royal Proclamation of 2003H16 which designated July 28th of every year as a commemoration of the “Grand Dérangement” and it began on July 28th 2005) stated this:

- “Assumptions

The Acadians were held to be British subjects (50) by the memorandum of Judge Jonathan Belcher” - “Genocide [...]

4. Violation of customary international law regarding treatment of prisoners of war: If we assume that the Acadians were French-subjects, the British violated the then existing customary international law regarding the treatment of prisoners of war. (103)”

A transcriptionH17 of Judge Jonathan Belcher's memorandum dated July 28, 1755 (in English and French) can be viewed at the Free Library by Parlex Website. Below are two excerpts from the Website of his ruling:

- “By their conduct from the Treat of Utrecht to this day they have appeared in no other light than that of Rebels to His Majesty, whose Subjects they became by virtue of the Cession of the Province and the Inhabitants of it under that Treaty.”

- “As to their conduct since the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 - Tho it was stipulated that they should remain on their lands on Condition of their taking the Oaths, within a year from the date of the Treaty”

Belcher made a grave error of law by wrongly using a legal agreement between Nations. That is, the Treaty of Utrecht to support his claim that Acadians were British Subjects.

Belcher would have known that the Edict by Queen Anne was not a legal binding document or a law. Therefore, he did not refer to her Edict in his ruling. He resorted to wrongfully paraphrasing the contents of Article XIV of the Treaty of Utrecht to give the appearance that the Acadians were British Subjects by it.

The misdeeds that Judge Belcher ruled factually that what the Acadians had done had little to do with the Acadians and are unfounded.

Furthermore, it was not the Acadians fault that Great Britain made a bad agreement with France by the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 regarding their interest in the ceded territory.

That is, in English dissatisfaction in how the French missionaries, the Aboriginals and French were able to conduct themselves under the treaty agreements. Also, of course, the Acadians able to remain in Acadie (Nova Scotia) legally as French Subjects according to what was the written law in the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713.

In the wording or articles of the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, no wording was found that supported that Acadians became British Subjects because the province was ceded, and/or stipulation that Acadians had to take an oath within a year from the date of the Treaty.

According to the wording in article XIV – Acadians remained French Subjects and would only lose their belongings legally if they had chosen freely to leave Acadie after one year in 1714.Therefore, needless to say, we know Acadians did not leave Acadie of their own free will.

The Royal Proclamation of 2003 is a start in the right direction. One thing right is in it not referring to the Acadians people as British Subjects. However, it does little to stop the dodging since 1755, in the question of law that the exile of the Acadians was unlawful. It is very unlikely that Great Britain would ever admit that the exile of the Acadians was unlawful.

Therefore, that would have to objectively take place or heard and decided in a setting like an International Tribunal. Lets remember, that it is declared here that Judge Jonathan Belcher used an international treaty wrongly in a unlawful manner to exile the Acadians in 1755.

Anyway, there is more in the next point 5 of this presentation, that is, on Judge Jonathan Belcher's mandate regarding the Acadians that was outlined in the letter dated October 29, 1754 from the Lords of Trade to Lieutenant Governor Lawrence.

The wrongs of history needs to be acknowledged clearly, otherwise those wrongs towards people will go without consequence, accountability and penalty, which will give room for new wrongs by others to be tolerated and repeated.

There are many opinions regarding the fate of the Acadians and what really happened back then. The world must be made aware correctly of history, which will ensure the remembrance of the terrible wrongs done to the Acadian people. Historians and people need to make sure if they indulge in the act of paraphrasing to make sure their information is from reliable source, and in their research to practice the motto or saying “trust but verify”.

- “Assumptions

Barthélemy Petitpas, William Shirley and The Treaty of Utrecht Continued

Another digitized bookD8 by Google is very revealing, it was published in 1869 and titled:

“Selections from the Public Documents of the Province of Nova Scotia: Published Under a Resolution of the House of Assembly Passed March 15, 1865”. On pages 264 and 265 of the book in the notes, the author Thomas Beamish Akins explains why he thinks the Acadians became British Subjects. He stated this:

“No mention is made, either in the Treaty or the Queen's letter, of a qualified allegiance. It is therefore clearly obvious that those who chose to remain, thereby became subjects of Great Britain, and were bound to take the Oath of allegiance to the Sovereign, when lawfully required.”What the author appears to have forgotten or missed is that according to the wording of the legal document the Treaty of Utrecht and its Article XIV, the Acadians were still legally French Subjects and didn't have to give any Oath of allegiance at all because the treaty did not stipulate it. The law was the Treaty. Actually, the Acadians made a non required concession according to the Treaty in giving a conditional oath. They were prepared to leave on several occasions when coerced to swear an unconditional oath. Acadians were prevented in leaving by Great Britain's authority. This was because Great Britain was scared if the Acadians left Nova Scotia (Acadie) they would reinforce and strengthen France's colonies of Canada and Île-Royale. The author's own selected documents for his book shows this. One of the times that the Acadians asked to leave Nova Scotia (Acadie) is recorded in a letter (page 173, book D8) dated September 6, 1749. The deputies from the French (Acadian) districts presented it at a council meeting.

Next is an excerpt of the letter:

“The inhabitants in general, Sir, over the whole extent of this country, have resolved not to take the oath which Your Excellency requires of us; but if Your Excellency will grant us our old oath which was given at Mines to Mr. Richard Philips, with an exemption for ourselves and for our heirs from taking up arms, we will accept it.

But if Your Excellency is not disposed to grant us what we take the liberty of asking, we are resolved, every one of us, to leave the country.”What follows is a excerpt from page 174 of Governor Edward Cornwallis answer to the Acadians:

“But you ought to know, that, from the end of the year stipulated in the treaty of Utrecht for the evacuation of the country, those who chose to remain in the province became at once the subjects of the King of Great Britain.

The treaty declares them such— The King of France declares, in the treaty, that all the French who shall remain in these provinces, shall be the subjects of His Majesty.”Of course, the treaty of Utrecht doesn't stipulate what Cornwallis communicated to the Acadians. He appears to have been clueless of the wording of the treaty or was he knowingly trying to make the Acadians agree to accept something which is obviously false. As said before, Acadians knew what was stipulated in the treaty. A lot of them would be capable in the Latin language, and if needed, they had available complementary consultation in having the expertise of their priests. Indeed they could verify in Latin that their French translation and interpretation of the treaty of Utrecht was correct.

However, in 1750, Cornwallis' policy resulted in many Acadians deciding that they wanted to leave and go to Île Saint-Jean. But they were being detained. They were told to sow their fields which they did and after they were refused because no passports were being issued. This is according to an answer to the Acadians by Governor Edward Cornwallis during a Council held with the Governor on March 25, 1750 (see pages 189 to 192 of book D8).

This leads to another excerpt of page 267 which is another note in the book (D8) by the author:

“The term "Neutral French" having been so frequently applied to the Acadians in public documents—their constant denial of an unqualified oath ever having been taken by them, and the reiterated assertions of their priests that they understood the oaths taken from time to time, in a qualified sense, (by drawing a distinction between an Oath of fidelity and one of allegiance,) led the Governors at Halifax, in 1749, and at subsequent periods, erroneously to suppose that no unconditional Oath of Allegiance had ever been taken by the people of Acadia to the British Crown.”What the author had failed to take into account is that the Governors didn't error. The reason is that King George II and the Lords of Trade knew there was a legality issue with the oaths. That is the oath's verbal part or the clause that Governor Phillips promised to the Acadians – to not have to bear arms. Governor Phillips was a representative of the King of Great Britain and could not mislead the Acadians or his King in his wish in having the Acadians freely and in a truthful manner become his Subjects. Also, there was a problem with the written part of the oath he gave. In a letter dated May 20, 1730 from Mr. Secretary Popple at Whitehall to Governor Phillips, Popple brought this to governor Phillips attention, the following is an excerpt (see book D8 pages 84 and 85) of the letter:

“Sir — You will perceive by the first paragraph of the letter from My Lords Commissioners for Trade and Plantations to you of this days date that their Lordships wish the Oath which the French Inhabitants at Annapolis have voluntarily taken had been in more explicit Terms, and therefore I am to observe to you that by the words of that Oath, the French do not promise to be faithful to His Majesty.”In a letter (see pages 87 to 88 in book D8) dated November 26, 1730 Governor Phillips wrote to the Lords of trade. Next is excerpt of that letter:

“I am sorry to find Your Lordships think the Oath which the Inhabitants of this River have taken not to be well worded, I used my best understanding in the forming of it and thought I had made it stronger then the original English, by adding the words, "en foi de Chrétien" and "que je reconnois" &c., the word fidèle is the only one I could find in the dictionary to express allegiance and am told by French men that both it and obéir govern a dative case, and the conjunction, et, between makes both of them to refer to the Person of the King, according as I have learned grammar, and I humbly conceive that the jesuits would as easily explain away the strongest oaths that could be possibly framed as not binding on papists to what they call a Heretic. Your Lordships will observe the oath that has been afterwards given to the body of the Inhabitants up the Bay of Fundy, to be varied; it was upon occasion of their thinking the other too strong. I believe Your Lordships will think this not liable to the same objection as the other, and not at all weakened in the alteration.”Furthermore, nothing could be more clearer on the Lords of Trade position about the Treaty of Utrecht and an unconditional oath regarding the Acadians. In a letter dated October 29, 1754, the Lords of Trade at Whitehall wrote to Lieutenant Governor Lawrence. An excerpt (see book D8 pages 236 & 237) of the letter states this:

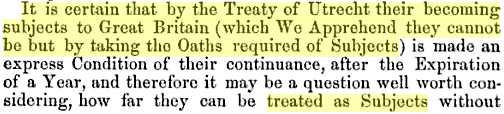

Above transcribed freely: It is certain that by the Treaty of Utrecht their becoming subjects to Great Britain (which We Apprehend they cannot be but by taking the Oaths required of Subjects) is made an express Condition of their continuance, after the Expiration of a Year, and therefore it may be a question well worth considering, how far they can be treated as Subjects without taking such Oaths, and whether their refusal to take them, will not operate to invalidate the Titles to their Lands; it is a question, however, which We will not take upon ourselves absolutely to determine, but could wish that you would consult the Chief Justice upon this Point, and take his Opinion, which may serve as a foundation for any future measure it may be thought advisable to pursue with regard to the Inhabitants in general. As to those of the District of Chignecto, who are actually gone over to the French at Beau Sejour, if the Chief Justice should be of opinion that by refusing to take the Oaths without a reserve, or by deserting their Settlements to join the French, they have forfeited their Title to their Lands, We could wish that proper Measures were pursued for carrying such Forfeiture into Execution by legal Process, to the end that you might be enabled to grant them to any persons desirous of settling there,

The Chief Justice Jonathan Belcher did not follow the mandate issued by the Lords of Trade. To be perfectly clear and well worth repeating.

The first part of Belcher's mandate was: “how far they [les Acadiens] can be treated as Subjects without taking such Oaths, and whether their refusal to take them, will not operate to invalidate the Titles to their Lands”.

The second part of Belcher's mandate was to decided about the Acadians from the District of Chignecto who had deserted their Settlements: “If the Chief Justice should be of opinion that by refusing to take the Oaths without a reserve, or by deserting their Settlements to join the French, they have forfeited their Title to their Lands”.Obviously, the Chief Justice of Nova Scotia Jonathan Belcher's did the opposite to what the Lords of Trade had declared. Belcher ruled that the Acadians were British Subjects according to his wrongful interpretation of the Treaty of Utrecht as previously described. In other words, Belcher's mandate from the Lords of Trade was simply to determine in accordance to the Treaty of Utrecht could the Acadians still own land if they were not British Subjects (treated as Subjects does not mean legally being Subjects).

Of course the Acadians could still own land according to what was stipulated in the Treaty. As said before there was nothing in the Treaty of Utrecht that compelled the Acadians to swear oaths to Great Britain, and or lose their possessions if they remained in Nova Scotia (Acadie). The Treaty had no stipulated time limit on that matter.

This brings us back in this presentation with the facts presented here that the exiled Acadians were legally not British Subjects according to the Treaty of Utrecht. Thus, they should have been treated as prisoners of war. Next is an excerpt of page 278 which is another note in the book (D8) by the author:

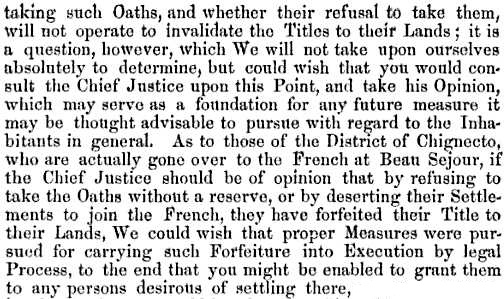

Above transcribed freely: * The French Acadians who were sent to Pennsylvania, petitioned the Governor and Council of that Province, in Sept. I756, to be treated as prisoners of War, and to be permitted to join their own nation, and from the tenor of their petition it would appear they did not wish to become settlers in that Province. The Governor and Council, however, on reference to Governor Lawrence letters, declined to treat them as prisoners of War and subjects of the French King, but as subjects of the King of Great Britain, and recommended the House of Assembly to "provide for them in such a manner as they should see fit."— Colonial Records, Pcnn., vol. 7. p. 241. They appear to have received better treatment at the hands of the Government of Philadelphia than was accorded to them in some of the other Provinces.

The author's reference to the Pennsylvania petition dated September 2, 1756 is available on pages 239 to 241 from a digitized bookD9 by Google titled: Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania: From the Organization to the Termination of the Proprietary Government. [Mar. 10, 1683-Sept. 27, 1775], Volume 7.

The Acadian men who are listed on the Pennsylvania, petition of September 2, 1756 may have been involved with another petition (see source H15*1). It was in 1760 to the King of Great Britain for a legal hearing. Another digitized bookD10 by Google titled: An Historical and Statistical Account of Nova-Scotia, Volume 1. The author Judge Thomas Chandler Haliburton refers to the petition in pages 183 to 195 and expressed his very poignant comments of the event at page 196.

Someone may ask what does this point or chapter of this presentation have to do with Bathélemy Petitpas? To have their way with him from 1745 to 1747, Great Britain and its colonial force by Governor William Shirley illegally declared Bathélemy Petitpas a British Subject by the Treaty of Utrecht. This allowed Britain to avoid giving him the protection and treatment required to a prisoner of war by International law.

About 10 years later, Great Britain and its colonial force by Judge Jonathan Belcher's ruling illegally avoided International Law in the same way again when he wrongfully declared that all the Acadian children, women and men by the Treaty of Utrecht were British Subjects instead of being French Subjects and prisoners of war.

William Shirley and Barthélemy Petitpas Continued

William Shirley had declared war against the Amalécite [Malecite] and Mi’Kmaq Nations in 1744. He offered a payment out of the Public Treasury for producing the scalp(s) to prove their deaths. The Online Massachusetts searchable descriptive index Archives has a documentH1. The summary of the document reveals:P2.P8 “PROCLAMATION BY GOV. WILLIAM SHIRLEY CALLING FOR VOLUNTEERS TO FIGHT AGAINST THE ST. JOHNS AND CAPE SABLE INDIANS. GOVERNOR SHIRLEY ENCOURAGED SCALPING AND INCLUDED THE SET BOUNTIES FOR SCALPS AND OTHER PLUNDER.” William Shirley should have been aware that Barthélemy Petitpas was Mi'Kmaq, and did he mistake Barthélemy for someone else? Wasn't Barthélemy the same person who received 3 years of schooling at Harvard in Boston at the expense of Great Britain? The apparent education was due to the humanitarian efforts of his father Claude II who negotiated the release of English prisoners in the late Indian war. He paid for the release with his own money. This is according to interpretation of an English (reference 59) record by Emma Lewis Coleman in 1925. Her bookH2 was used as a reference (see P11.P1) for Claude II and Barthélemy Petitpas' biographies.The reality was that William Shirley thought Great Britain owned Barthélemy Petitpas. Barthélemy Petitpas did not dodge his duties. Furthermore, it is difficult to think that William Shirley would not be aware and mention that Barthélemy Petitpas’ French employment and title was that as Interpreter for the Indians. He was employed in this capacity since 1733 after his father’s death. Claude Petitpas II held the position prior to Barthélemy Petitpas' appointment. William Shirley from a military point should have known that Claude Petitpas II also like his son Barthélemy had emigrated elsewhere to Île Royale (Cape Breton Island).

It must be noted that the English wanted to end France’s friendship they had with the Mi'Kmaq Nation. William Shirley, being at war with France, would undoubtedly know that he could advance his position if the French were to lose their Interpreter for the Indians. This would have resulted in France losing Amalécite (Malecite) and Mi’Kmaq communication and the ability to conduct diplomatic negotiations. Therefore, this would have been an effective military and political strategy.

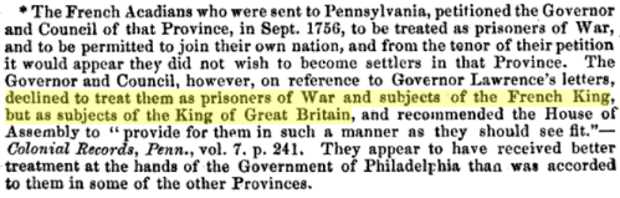

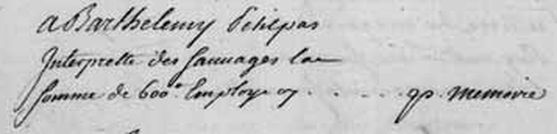

The LAC Website has 11 digitized images of the original handwritten documentB6. This is an invoice for services rendered by Major Officers and other necessities for the colony during the year 1745. This document was dated August 27, 1746 . The details of payment regarding Barthélemy Petitpas as Interpreter for the Indians is on page 5 of 11 (Second expense from the bottom of the page). Below is an excerpt about his employment:

Above translated freely: To Barthelemy Petitpas, Interpreter for the Indians, the Employment amount of 600#

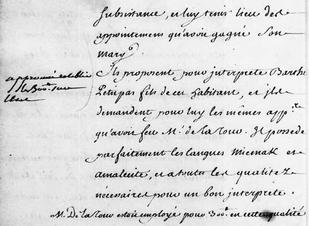

The How and When of The Petitpas' as Interpreter for The Indians

One of the records at LAC Website, is a handwritten documentB7 (see folio 5 & 5v) resumé of a letter dated November 16, 1732. It is the application and recommendation for approval of Barthélemy Petitpas as Interpreter for the Indians to replace his father Claude II who died. This letter confirms that Claude Petitpas II died in 1732, at DCB Online his biography states “He died probably some time between 1731 and 1733”. Also, the letter says that Barthélemy Petitpas has a perfect command of the Mi’Kmaq and the Amalécite [Malecite] languages, and has all the qualities necessary to be a good interpreter.Note: It is not mentioned at DCB Online in Barthélemy's biography that he could speak the Indian language Amalécite [Malecite]. Also, Author Isabelle Ringuet brings this to her readers' attention in her thesisB8 at the bottom paragraph on page 73B8c (also, see below P12.P1). Below at (P17.P25) by translated excerpts this letter dated November 16, 1732 is explored further.

Another LAC Website recordB9 (scope & content) dated May 19, 1733 is the approval of Barthélemy Petitpas as Interpreter for the Indians.

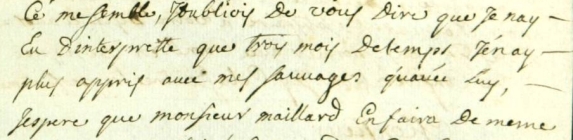

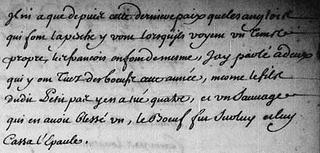

Father Maillard's Account of Barthélemy Petitpas' Death

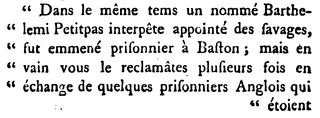

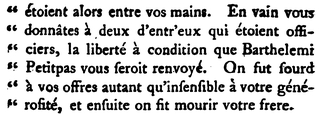

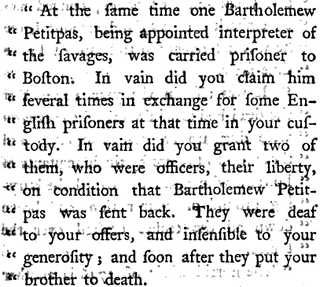

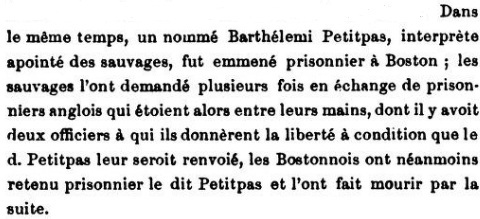

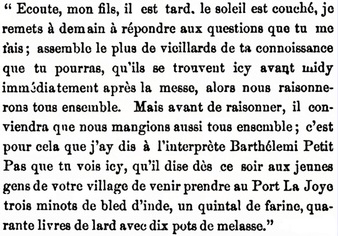

Pierre Antoine Simon MaillardA5 whose biography is at DCB Online, in an account wrote this: “About the same time one named Bartholomew Petitpas, an appointed savage-linguist, was carried away prisoner to Boston. The savages have several times demanded him in exchange for English prisoners they then had in their hands, of whom two were officers, to whom they gave their liberty, on condition of the Bostoners returning of Petitpas; whom, however, they not only kept prisoner, but afterwards put to death.”This research discovered no Governmental documentary evidence record that the Bostoners executed Barthélemy Petitpas. However, Father Maillard says in his manuscript that Barthélemy Petitpas was carried away prisoner to Boston about July 1745. The records indicate that he died in January 1747. During that time Barthélemy would be in his late fifties, and he would have spent approximately 18 months in the Boston dungeons before he died or was put to death. In any event, Barthélemy incarceration in the Boston dungeons could be viewed as a sort of death sentence in itself. That is how could a man of his age survive for numerous years in the Boston dungeons. Also, this leads one to think that the people keeping him in captivity would be quite aware of Barthélemy's thin chance of survival in the dungeons at his advanced age.

The above reference to the manuscript by Pierre Antoine Simon Maillard was translated from French to English. In the book, there are 4 pieces of writing which the first two are attributed to Father Maillard. The piece of writing that refers to Barthelemy Petitpas is titled Memorial of the Motives of the Savages, called Mickmakis and Maricheets, for continuing the war with England since the last peace. Dated Isle-Royal, 175-.. The book is titled: An Account of the Customs and Manners of the Micmakis and Maricheets Savage Nations, Now Dependent on the Government of Cape-Breton. This documentH3 is available on the Internet from Project Gutenberg Website. The original 1758 published book is now in the public domain and available from Google. The reference to Barthelemy Petitpas is on pages 64 and 65 of the original bookD2.

In his book published in 1870 for the French Complaints at page 43, Samuel Gardner Drake makes a reference about Barthelemy Petitpas that they "finally put him to death". There is more about his book below at point 11. In his book at page 44, he states: "These accusations or charges are the substance of speeches delivered to the eastern Indians by the Count de Raymond, to inflame them to prosecute the war".

Obviously, the accusations or charges written were a translation from French to English. Fortunately, for the sake of authenticity of the French accusations and the accuracy of translation, there are two books of French origin which have the content of the accusations. However the authors of the books differ in who is the author of the piece of writing.

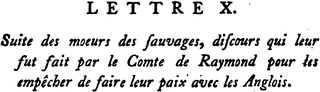

The first bookD3A was written in French by Thomas PichonA6 published in 1760 and titled: Lettres et mémoires pour servir à l'histoire naturelle, civile et politique du Cap Breton. The letter (page 129, LETTRE X.) is titled Suite des moeurs des sauvages, discours qui leur fut fait par le Comte de Raymond pour les empêcher de faire leur paix avec les Anglois.

Next are the first book's excerpts of pages 129 (letter title), 133 and 134:

Excerpt translated freely

Excerpt translated freely

LETTER X.

Further to the customs of the Savages, the speech which was made for them by Comte de Raymond to prevent them from making their peace with the English.

At the same time, one named Barthelemi Petitpas, appointed interpreter for the Savages was taken prisoner to Boston, but in vain you asked for him several times in exchange for some English prisoners who were in your hands. In vain you gave two of which were officers among them freedom provided that Barthelemi Petitpas would be returned to you. They were deaf to your offers as insensible to your generosity, and afterwards they killed your brother.The 1760 French book written by Thomas Pichon was translated and published in English. The following from the 1760 English bookD3B is an excerpt from page 163 regarding Barthélemy Petitpas:

Excerpt transcribed freely

Excerpt transcribed freely

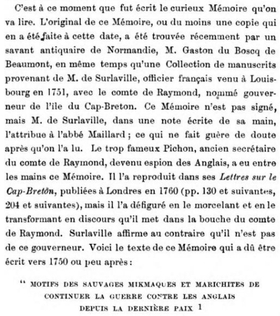

At the same time one Bartholemew Petitpas, being appointed interpreter of the savages, was carried prisoner to Boston. In vain did you claim him several times in exchange for some English prisoners at that time in your custody. In vain did you grant two of them, who were officers, their liberty, on condition that Bartholemew Petitpas was sent back. They were deaf to your offers, and insensible to your generosity; and soon after they put your brother to death.The second bookD4 was written in French by Father Henri Raymond CasgrainA7 which was published in 1897 and titled: Les sulpiciens et les prêtres des Missions-étrangères en Acadie. The letter (page 437, memoir) is titled MOTIFS DES SAUVAGES MIKMAQUES ET MARICHITES DE CONTINUER LA GUERRE CONTRE LES ANGLAIS DEPUIS LA DERNÈRE PAIX.

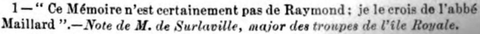

Next are 3 excerpts from the second book. The first excerpt has Father Casgrain's explanation of the evidence uncovered and his reasons why the memoir is attributed to Father Maillard. Also, the first excerpt from page 437 contains the memoir's title. The second excerpt, a footnote is still from page 437. The third excerpt from page 439 is the information from the memoir about Barthélemy Petitpas:

Excerpt translated freely: It is at this time that was written the curious memoir that we will read.

The original memoir, or at least a copy that was made at that time, was found recently by a antiquary scholar of Normandy, M. Gaston Bosoq of Beaumont. This was at the same time, along with a collection of manuscripts from M. Surlaville, a French oflicier who came to Louisbourg in 1751, with the Comte de Raymond, the appointed governor of the island of Cape Breton. This Memoir is not signed, but M. de Surlaville in his hand written note, attributed it to Maillard, which there was little doubt after we read it. The too famous Pichon, former secretary of Comte de Raymond, who became a spy for the English, had this memoir in his possession. He reproduced it in his Letters about Cape Breton, published in London in 1760 (pp. 130 and following, 204 and following). But he disfigured it by fragmenting and turning it into speech and puts into the mouth of Comte de Raymond. Surlaville affirms the contrary, it is not the governor.

Here is the text of this Memoir that must have been written in 1750 or soon after:

Excerpt translated freely: It is at this time that was written the curious memoir that we will read.

The original memoir, or at least a copy that was made at that time, was found recently by a antiquary scholar of Normandy, M. Gaston Bosoq of Beaumont. This was at the same time, along with a collection of manuscripts from M. Surlaville, a French oflicier who came to Louisbourg in 1751, with the Comte de Raymond, the appointed governor of the island of Cape Breton. This Memoir is not signed, but M. de Surlaville in his hand written note, attributed it to Maillard, which there was little doubt after we read it. The too famous Pichon, former secretary of Comte de Raymond, who became a spy for the English, had this memoir in his possession. He reproduced it in his Letters about Cape Breton, published in London in 1760 (pp. 130 and following, 204 and following). But he disfigured it by fragmenting and turning it into speech and puts into the mouth of Comte de Raymond. Surlaville affirms the contrary, it is not the governor.

Here is the text of this Memoir that must have been written in 1750 or soon after:

" MOTIVES OF THE MIKMAQUES AND MARICHITES SAVAGES FOR

CONTINUING THE WAR AGAINST THE ENGLISH

SINCE THE LAST WAR 1

Above transcribed freely: 1- " This memoir is certainly not from Raymond: I believe it is from abbot Maillard".-Note from M. de Surlaville, the major of the troupes at l'Île Royale.

Above transcribed freely: At the same time, one named Barthélemi Petitpas, appointed interpreter for the Savages was taken prisoner to Boston, the Savages had asked for him several times in exchange for some English prisoners who were in their hands, which two were officers that they gave them freedom provided that the said Petitpas would be returned. However, the bostoners kept the said Petitpas and afterwards killed him.In short, Father Casgrain thought that the memoir shouldn't be attributed to a speech given to the Indians by the Comte de RaymondA8 the Governor of Île Royale. However, it is the opinion from this research there is a very uncomplicated explanation, Comte de Raymond was fairly new in the Colony. Thus he listened and utilized the information that Father Maillard and other persons provided for his motivational speeches to the Indians.

Thomas Pichon wrote that he was only the editor of the letters in his book. They were written at Louisbourg commencing from 1752 to the siege of that place. He titled them which the letter X is importance to this research on Barthélemy Petitpas. The writer of letter X, had promised an example of a speech for his reader that was given to the Indians. The speech was included as part of the letter. No editorial notes were found in the letters.

This is a sharp contrast to how the above reference book titled An Account of the Customs and Manners of the Micmakis and Maricheets Savage Nations, Now Dependent on the Government of Cape-Breton (H3 & D2) depicts the French complaints. This book has many editorial comments (in square brackets) within the four pieces of writing. In most cases these comments try and explain away the recounting of the awful events and accusations against the English. This is done by putting the blame elsewhere in a sarcastic manner. The book depicts the Indians as uncivilized, barbaric and dismisses disrespectfully their customs. The book's first piece of writing as said before is attributed to Father Maillard. However there is suspicion from this research that the letter is not from him. Its first four paragraphs appear to contain summary of the start of a lengthy letter, that Father Maillard wrote on the subject of the Indian ways of those parts of the country. He had written it for his superior M. de Lalane in Paris. This letter is discussed further below at point P19.P3.

As stated previously, this research discovered no Governmental documentary evidence record that the Bostoners executed Barthélemy Petitpas. However, the note from M. de SurlavilleA9 the major of the troupes at l'Île Royale attributed the memoir to Father Maillard. Plus the fact that a copy of the memoir was in M. de Surlaville possession puts credence that Barthélemy Petitpas was put to death.

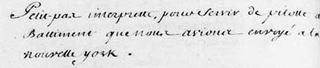

Barthélemy Petitpas' Biography and The Year 1722

Eric KrauseP18.P4 (krause House Info-Research Solutions) - The Build History of Port Toulouse, Isle Royale, for The Louisbourg Institute of Cape Breton University, had a summary record about Barthélemy Petitpas. This summaryG2 was on the Official Research Site for the Fortress of Louisbourg Website ("1721 - November 05"). It states that Barthélemy lost his civil court case relating to the confiscation of his schooner and cargo. His sentence was upheld on appeal in 1722: “Later, in 1722, the Council confirmed the sentence, and he was ordered to pay 1000 pounds [livres] plus court expenses.”

From the record, it appears that Barthélemy Petitpas:- was a resident of Port Toulouse and at that time was living under French domination.

- was working in some capacity as interpreter for the Indians for the French.

- was conducting himself in a civil manner, within one day, he appealed his sentence of November 4, 1721.

Therefore, it would be most unlikely that the French had to capture him. In his biography on the DCB Online Website, paragraph 4, it is outlined that he was captured. He may have been arrested but doesn't the word capture seem very bold and a term saved for an enemy?

However in 1925, Emma Lewis Coleman in her book wrote: "but M. de Saint-Ovide61 found a way to get the young man out of the hands of the English and entice him to Quebec". This was regarding Barthélemy Petitpas for the year 1722. Later in this document, there is more about her book in more detail and the fact that the young man's first name was not mentioned in her reference. This is according to copies of original documentation reviewed during this research.

Also, the first name of the young Petitpas was not mentioned in the following two references from Barthélemy's biography at DCB Online are AN, Col., B, 45F4, ff200F4f, 205; and C7, 244B10*3. These records are at Archives Canada-France & Library and Archives Canada Websites. As previously written, the young man is not referred to by first name, just as Petitpas and Le Nommé Petitpas son of an inhabitant from Acadie. The first above reference (ff200 - Item 201) is dated 1722:

![Hyperlinked excerpt from an Online document from the Canada-France Archives at LAC about the son of le nommé [the one named] Petitpas](img-r/17221215.jpg) Excerpt translated freely: To M. de Beauharnois - At Versailles Dec. 15, 1722 - Mister the Council made M. de Regens aware of your notification you gave about the arrival at Rochefort of the son of the Nommé Petitpas. A French inhabitant of Acadie who boarded on the flutte le chameau [name of a ship]. The reason which was determined by Vaudreüil and Begon to send this young man at the King's expense. S.A.A. has judged for the same reason that it is just to have him learn piloting, and to have him serve when he his capable.

You will conform to the comments of S.A.R.. You need to be aware of his conduct and pay attention that he doesn't escape to board English vessels.

Excerpt translated freely: To M. de Beauharnois - At Versailles Dec. 15, 1722 - Mister the Council made M. de Regens aware of your notification you gave about the arrival at Rochefort of the son of the Nommé Petitpas. A French inhabitant of Acadie who boarded on the flutte le chameau [name of a ship]. The reason which was determined by Vaudreüil and Begon to send this young man at the King's expense. S.A.A. has judged for the same reason that it is just to have him learn piloting, and to have him serve when he his capable.

You will conform to the comments of S.A.R.. You need to be aware of his conduct and pay attention that he doesn't escape to board English vessels.The scope and content for the second above mentioned reference (C7, 244*3) indicates: Petitpas - Son of a inhabitant of Acadie - 1727, his transfer from Boston to Québec, then to Martinique. This is a 4 page file with different dates – 1722, 1723 & 1727:

Cover Page

Page 1

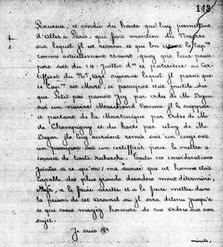

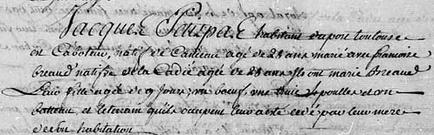

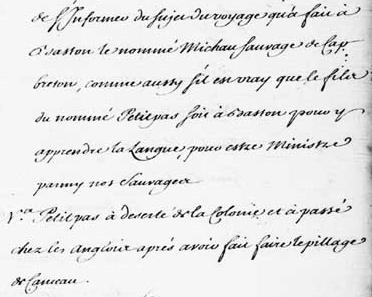

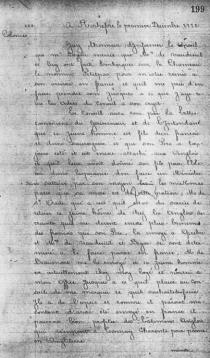

![Hyperlinked excerpt of the cover page from an Online 1727 document from LAC about le nommé [ the one named] Petitpas a son of an inhabitant from Acadie](img-r/pg1-1727.jpg) Excerpt translated freely: M. de Vaudreüil and Begon decide in 1722 about Le Nommé Petit pas son of a French inhabitant of Acadie. He was attached to the English and was sent by his father during the last war to Boston. There the English paid for his subsistence and maintenance for three years with insight to make him a Minister and win over the MiKmaKe [Mi'Kmaq] Nation and make them change their religion. M. St Ovide, the Governor of Île Royale found the means to withdraw this young man from the English, and sent him to Quebec.

He made him understand that we were putting him in the Seminary. But this young man testified upon his arrival at Quebec that he did not want to enter the ecclesiastic [Clergy] order. To prevent him from returning to Boston, M. de Vaudreüil and Begon determined to send him to France by la flutte le chameau [name of a vessel] in 1722. This was to M. de Beauharnois place

Excerpt translated freely: M. de Vaudreüil and Begon decide in 1722 about Le Nommé Petit pas son of a French inhabitant of Acadie. He was attached to the English and was sent by his father during the last war to Boston. There the English paid for his subsistence and maintenance for three years with insight to make him a Minister and win over the MiKmaKe [Mi'Kmaq] Nation and make them change their religion. M. St Ovide, the Governor of Île Royale found the means to withdraw this young man from the English, and sent him to Quebec.

He made him understand that we were putting him in the Seminary. But this young man testified upon his arrival at Quebec that he did not want to enter the ecclesiastic [Clergy] order. To prevent him from returning to Boston, M. de Vaudreüil and Begon determined to send him to France by la flutte le chameau [name of a vessel] in 1722. This was to M. de Beauharnois place

Top of Page 1: Signature of [?] September 8, 1727

In the margin of Page 1: Petitpas – Approve the proposal of M. de Beauharnois sending to la Martinique to serve as a soldier – RPage 2

![Hyperlinked excerpt of page 2 from an Online 1727 document from LAC about le nommé [the one named] Petitpas a son of an inhabitant from Acadie](img-r/pg2-1727.jpg) Excerpt translated freely: to take care of him until he received orders from the Navy Council. M. de Beauharnois gave advice to the Navy Council who approved on January 5, 1723 to have him learn piloting. He was paid 50.# in the port for his maintenance, food and extraordinary expenses in the port, and 18. [#] per month to embark as a pilot.

Excerpt translated freely: to take care of him until he received orders from the Navy Council. M. de Beauharnois gave advice to the Navy Council who approved on January 5, 1723 to have him learn piloting. He was paid 50.# in the port for his maintenance, food and extraordinary expenses in the port, and 18. [#] per month to embark as a pilot.

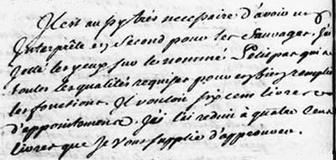

I remark since 1723 until now [Sept. 8, 1727], he had Petit pas payed 50.# per month during the time he stayed at [?]. After the orders, he received only 18.# at sea when he embarked in the capacity as a pilot. Since the last campaign that he did on the Caisseau, the françois, he was nearly always sick and since two months communicates he wants to reestablish. What a bad subject

In margin of Page 2: From April 26, 1723Page 3

![Hyperlinked excerpt of page 3 from an Online 1727 document from LAC about le nommé [the one named] Petitpas a son of an inhabitant from Acadie](img-r/pg3-1727.jpg) Excerpt translated freely: who attaches to nothing but women and wine which he is lost to. He is so furious when he is drunk, he is capable of doing some bad tricks. I propose to send him to Martinique or St Dominique to have him serve in the capacity as a soldier of new enrollment. If that is approved, they will make him board the Portefais [name of a vessel].

Excerpt translated freely: who attaches to nothing but women and wine which he is lost to. He is so furious when he is drunk, he is capable of doing some bad tricks. I propose to send him to Martinique or St Dominique to have him serve in the capacity as a soldier of new enrollment. If that is approved, they will make him board the Portefais [name of a vessel].It is challenging to envision Claude Petitpas II considering and agreeing to changing his faith and encouraging his children to do so - That is to change from Catholicism to the Protestant faith, and his son convert the whole Indian population. In addition, the above documents seem to hint that the young man is not Barthélemy Petitpas.

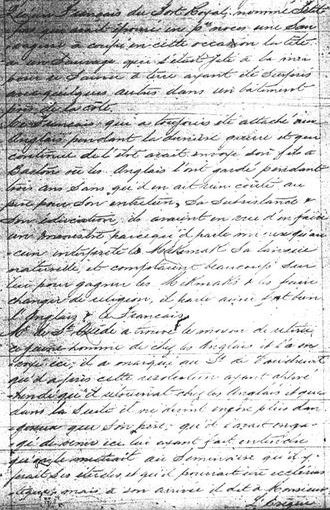

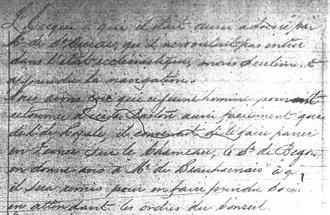

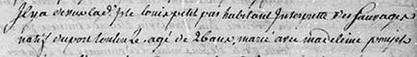

Barthélemy Petitpas was Mistaken for Someone Else

Rumor and stories stem largely from the documentation written in 1722 & 1727. M. de St Ovide the Governor of Île Royale is referred in the document dated 1727. He had a plan to save the French Colony and get Barthélemy Petitpas out of the hands of the English. Apparently, Barthélemy is transfered to different places under French Authority. As noted above, the file dated 1727 available at LAC Website refers to a Petitpas without a first name and the year 1722.The Archives nationales d'outre-mer at Aix-en-Provence France has a documentH11 dated February 14, 1730 from Martinique. The next excerpts of pages 23 & 24 are about a soldier (pilot) named Petitpas sent to them from Canada:

Above translated freely: However Monseigneur, we are obliged to ask you to find it good that we sent back to France two of our soldiers. One is Petitpas, he is a pilot who has been sent here from Canada. There is nothing more dangerous than a soldier pilot here, he can promote the removal of batteaux that our soldiers are subjected to. During the traverse of the revolters at St Thomas, Ste Marie [Sainte-Marie Martinique] always regret in not having Petitpas, he is also a very bad subject capable of`a bad thing.

According to Barthélemy's biography at DCB Online Website in paragraph 4 and 5, it says that: “In 1722 Saint-Ovide sent him to the seminary of Quebec” and “He was released from prison in June 1730, still proscribed from returning to New France.”.

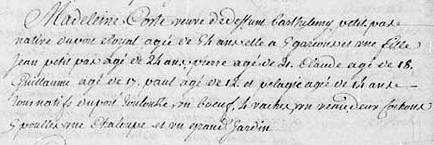

In 1715, Barthélemy was married in the Catholic faith at Port Royal (Annapolis Royal). His children were born in Port Toulouse, Île Royale. His eldest child was daughter Madeleine born about 1717, then Joseph 1723, Jean 1728, Pierre 1731, Claude 1734, Guillaume 1735, Pelagie 1738 and Paul 1740.

How can the above mentioned documentation dated 1727 and the biography of Barthélemy be accurate if the birthdays of his children are correct? Further puzzling would be how his wife, Madeleine Coste, endured his banishment, bearing two of his children during that time. Moreover, how could Barthélemy Petitpas, his wife and children appear on the Port Toulouse Censuses for the years 1717, 1720, 1724 and 1726? The census recordsG3 were at the Louisbourg Institute of Cape Breton University Website and at LAC.

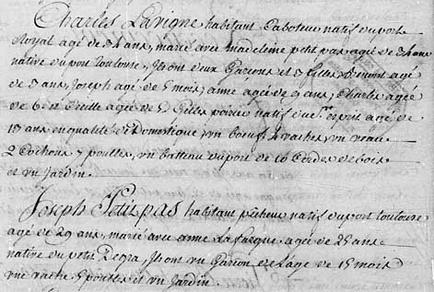

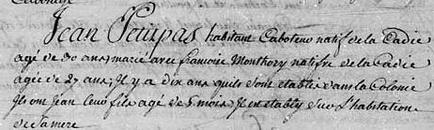

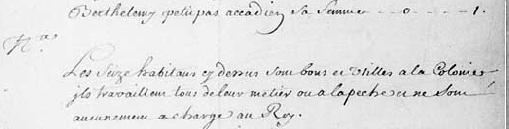

In the 1717 census of the new colony of Île Royale it is reported that Barthélemy Petitpas was of high esteem. He was one of 16 (out of 26) inhabitants that were self-sufficient and at no cost to the King of France. The document is at LAC . The following is an excerpt of the documentB11:

Above translated freely: Barthelemy Petitpas acadian...His Wife...0 [boys]...1 [girls]

The sixteen above inhabitants are good and useful to the Colony. They work at their trade or at fishing and are in no way a charge to the KingLAC has the 1720 census for the new colony of Île Royale. The following is an excerpt of the documentB12:

Above translated freely: Barthelemy Petitpas .. 4 [boats used for fishing]...1 [Wife]...2 [boys]...2 [girls]

Note: Barthélemy's brothers Joseph & Paul were living in the same dwelling for the census years 1724 & 1726. This takes away some suspicion that it was Joseph or Paul who was exiled in 1722, and Barthélemy was mistaken for one of them in his biography at DCB Online. The indefinite exiles of three of the four brothers are described below at P17.P5 in a letter dated November 3, 1728. In 1722, Barthélemy would be close to 35 years old which would not be considered that young for a man in those times. Paul would have been about 27 years old and Joseph 23.

The LAC Website has the 1724 census for the colony of Île Royale. It is titled the “Recensement général des habitants établis à l'Isle Royalle fait en l'année 1724”. This 1724 censusB13 item11 shows the three brothers as residents of Port Toulouse. Item 12, shows Claude Petitpas II without any boy(s) above 15 years old living with him. His children would be from his second marriageH4, which took place on January 7, 1721. His 19 year old son Isidore, from his first marriage doesn't appear anywhere on the 1724 census. See below two excerpts:

Also, the LAC Website has the 1726 census for the colony of Île Royale. It is titled the "Recensement général des habitants établis à l'Isle Royalle fait en l'année 1726". This 1726 censusB14 (item 11) shows the three brothers as residents of Port Toulouse - see below excerpt:

Could someone else have been mistaken for Barthélemy Petitpas in his biography at DCB Online? Could the answer be in which brother does not appear on the above census years 1724 & 1726? Could this person be “Isidore” the youngest son of Claude Petitpas II and Marie-Thérèse? Could Isidore Petitpas be the young man referred to in the document file (c7, 244) dated 1727 available at LAC Website? However, in the above excerpt of the 1726 census for the colony of Île Royale, Claude Petitpas the Merchant has one boy above 15 years old living with him.

Author Isabelle Ringuet makes an interesting reference about Isidore Petitpas:

“De plus, Isidore Petitpas, fils de Claude, fait des études à Harvard”Above translated freely: In addition, Isidore Petitpas, son of Claude, did studies at Harvard

The source is in her 1999 thesis document named Les stratégies de mobilité sociale des interprètes en Nouvelle-Écosse et à 1'Ile Royale, 1713 -1758 (LAC Website) – see line 6 from the top of page 98B8d.

The 4 Petitpas brothers' first names and their ages are listed in a 1708 census documentC3. This is at Website 1755 The History and the Stories by the Centre D'Études Acadiennes of the Université de Moncton. Then back in 1708, Isidore was 5 years old, Joseph 9, Paul 13 and Barthélemy 21.

The Indian family above is referred in the census made in November, 1708. LAC Website lists their copy of the original census as on microfilm reel M-1680.The original Indian census documentH7 is part of Edward E. Ayer(1841-1927) collection which is in the possession of the Newberry Library. An original copy of page 17 was obtained for this research:

Emma Lewis Coleman and The Petitpas' BiographiesP6.P1

In 1925, Emma Lewis Coleman wrote a book titled New England Captives Carried to Canada Between 1677 and 1760 During the French and Indian Wars. Volume one of this book was used for Claude Petitpas II's and his son Barthélemy's biographies at DCB Online Website Viewed in Volume One at pages 97 & 98:Above transcribed freely:: [Page 97 & Page 98]

Claudius Petitpas, 1720.